Produce, Re-use, Recycle…

A partial copy and posterisation of an original – out of copyright – painting (Louvre, Paris).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabrielle_d%27Estr%C3%A9es_et_une_de_ses_s%C5%93urs

Because of its surroundings it constitutes contextual reportage of both images [also see Abstracted below].

In 2005 an 8 year old girl was told by a security guard to stop sketching Picasso and Matisse paintings as ‘they’re copyrighted’ (Jardin 2005). So what is a copy and how much new, creative work is required to term the work as ‘influenced by’, or an ‘homage’? Is her version in a different medium a copy? Clearly it is copying the original to some extent, but equally clearly it doesn’t have commercial value that would impact on either Matisse’s or Picasso’s estates. These extreme examples may seem ludicrous, but they seep into the consciousness of the public. As I will illustrate, some ‘copies’ are artworks in their own right, albeit derived from other creations. However, despite a change of medium and/or style, they can have a commercial impact and fall foul of copyright restrictions.

© Orietta.sberla, from Wikimedia Commons

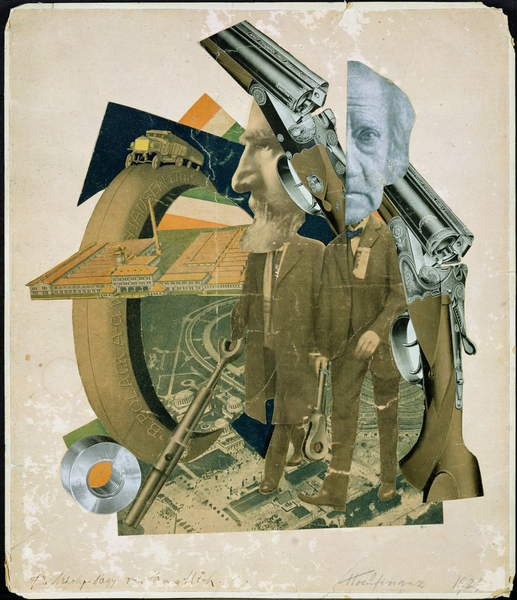

Marcel Duchamp tested the re-presentation of vernacular objects with a reclaimed urinal placed in an art gallery. He later added a moustache and goatee to a cheap print of Da Vinci’s – out of copyright – painting of the ‘Mona Lisa’.¹ Such re-appropriation and re-working has a long history in art. Changes in context create changes in meaning; re-appropriation creates changes in authorship and therefore in intent. Producing collages overtly ‘borrows’ from others to re-form context and meaning. Collage came of age at the start of the mass reproduction of images, e.g. Hanna Höch’s Dadaist works of the 1910s. Revived in the Pop art era of the1950s-1960s (see Peter Blake or Richard Hamilton), they became more playful and self-conscious in the postmodern era e.g. Terry Gilliam’s cartoons for Monty Python.² Copying and manipulation have now become far easier, producing a proliferation in output, further complicating the issues of what constitutes a copy and an infraction. Much of Pop art’s borrowing and re-working was confined to out of copyright works, or ephemeral, commercial sources such as magazines. Once teasing, obvious and clearly an amalgamation of different works, today that clarity has clouded, with some artists happy to test the copyright of others by re-appropriating images unaltered.

Richard Prince worked in the tear-sheet library of the Time-Life group, eventually (mis) appropriating images from magazine ads for his own art (cropped to remove text and the advertiser’s references). Prince is most famous for his ‘Marlboro Man’³ images that he’s happily stated were ‘stolen’.⁴ Recent highly publicised cases have tested even Prince’s mettle at facing plagiarism charges (not for the first time). In 2016 an exhibition of images downloaded from Instagram without changes – merely re-presenting for the gallery wall – brought multiple lawsuits.⁵ Prince’s cachet means that he can command high prices for his prints of what he simply took from other people’s IG accounts. Such outright theft of art will always be controversial and attract litigation.

Abstracted

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CheShirtsMuseum.jpg

This picture of Plaza de la Revolución contains a metal sculpture that’s also based on Korda’s image. With the artwork photographed in context my image has ‘fair use’ within editorial usage, but not for commercial uses such as advertising. This is an important distinction between the ‘fair use’ policy of reporting on the observed, and the directly commercial intentions that copy originals, even when they are altered.

Homage

Homage is generally reverential, even if humorous: directly related to the original, yet reformed as a different entity. Post-modern re-workings of iconic artworks are saleable in their own right. In the recently published Double Take: Reconstructing the History of Photography (Cortis and Sonderegger 2018),⁹ the pair produced replicas of classic photographs by photographing scale models and scenery in their studio. Images in the book are shown alongside the sets that were used to create them, which acknowledges their source. One of these, a life-sized replica of American photographer William Eggleston’s (in) famous ‘Red Ceiling’ (aka ‘Greenwood, Mississippi’, 1973), was displayed for the public to take their own ‘copies’ [as seen at the OCA study visit to Format Festival, Derby in 2015]. Their images (and mine) replicate the original photographs without copying the actual image directly, but by reconstructing a visually similar scenario. A note at the end of the book says that they tried to trace all copyright holders to seek permissions: acknowledging that they could be breaching copyright.

While these reconstructions create realistic ‘copies’, Charles Woodard’s humorous cartoon versions of classic images The History of Photography in Pen & Ink are clearly based on the originals. However, while recognisable to those who know the images, they are very different in form from the originals: almost caricatures. This is a case of ‘influenced by’ an original. Has Woodard produced a homage, a pastiche, a rip-off or a reworking of the idea of the original? I would argue that these drawings – and Cortis & Sonderegger’s images – are a playful, fresh take on what the original images have become as cultural icons, rather than as images alone (Woodard 2012)?10

The passing of Pop art’s spirit

In a review of a Pop-art show that restricted press photography, Cory Doctorow asked ‘have the freedoms of the ‘pop art’ era passed’? These artworks and their current exhibition ‘both celebrate [by re-appropriating images] and deny ‘fair use’ at the same time’ (Doctorow 2007b). If, for example, owners of Andy Warhol’s prints can say they don’t want them photographed, do the owners of works whom Warhol plagiarised (e.g. Cambell’s soup cans) have the same rights over Warhol’s prints? It should be simple, but it isn’t. You might think that an institution such as the Tate could reasonably be expected to have these issues sorted out. If you visit their website to view Peter Kennard’s ‘Haywain with Cruise Missiles’ (1980)¹¹ the caption reads ‘© Peter Kennard’. Below that there is a link to ‘License this image’: do they mean Constable’s ‘Haywain’, or Kennard’s cold war, apocalyptic update?

How far would you go?

The flip side to these issues is to ask yourself how would you feel, about your creative work being used by someone else? Does it depend on its context, such as who uses it, how it is used, is it altered, is it captioned, is it credited to you, where is it shown, do they seek to profit from it, is it critiqued, is it praised? Then consider how that decision might alter if you depended on your creative talents to make a living. I suggest that when creating art that’s based on other people’s copyrighted work you should exercise caution: note the copyright holder and name the original work’s name and artist(s). Credit everything with appropriate citations (which we hope you’ll be doing anyway) and state that your usage is non-commercial.

Cortis, J. and A. Sonderegger (2018). Double take: reconstructing the history of photography. London, Thames & Hudson.

Doctorow, C. (2007b). Photo-bans at pop art shows — irony impairment, or Dadaism? https://boingboing.net/2007/11/13/photobans-at-pop-art.html

Accessed 22/10/11

Jardin, X. (2005). Stop sketching, little girl — those paintings are copyrighted! boingboing. C. Doctorow. USA. https://boingboing.net/2005/01/08/stop-sketching-littl.html Accessed 16/12/11

Kennedy, R. (2012). Shepard Fairey Is Fined and Sentenced to Probation in ‘Hope’ Poster Case. Artsbeat. New York Times.

Shepard Fairey Is Fined and Sentenced to Probation in 'Hope' Poster Case – The New York Times accessed 02/11/18

Kravets, D. (2011). Associated Press settles copyright lawsuit against Obama ‘Hope’ artist. Wired. Condé Nast.

Associated Press Settles Copyright Lawsuit Against Obama 'Hope' Artist | WIRED accessed 02/11/18

Woodard, C. (2012). The History of Photography in Pen & Ink, A-Jump Books.

Featured image: Prague Castle grounds © D Trillo 2005, A partial copy and posterisation of an original – out of copyright – painting (Louvre, Paris). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabrielle_d%27Estr%C3%A9es_et_une_de_ses_s%C5%93urs Because of its surroundings it constitutes contextual reportage of both images.

¹ https://www.wikiart.org/en/marcel-duchamp/l-h-o-o-q-mona-lisa-with-moustache-1919

² The ‘foot’ at the end of the opening credits (rotated and flipped) was from Bronzino’s Cupid https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Monty_python_foot.png

³ http://100photos.time.com/photos/richard-prince-cowboy

⁴ https://www.guggenheim.org/arts-curriculum/topic/cowboys

⁵ https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jan/04/richard-prince-sued-copyright-infringement-rastafarian-instagram

⁶ Andy Warhol’s ‘Marilyn Monroe’ image, originally from the film ‘Niagara’ (Hathaway 1953) is still being reproduced https://news.masterworksfineart.com/2017/10/10/andy-warhols-marilyn-monroe-series-1967

⁷ It has never been suggested that Obama, or his staff, knew that Fairey had copied the image.

⁸ Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez

⁹ See samples of these constructions at https://www.ohnetitel.ch/icons/

10 https://www.photobookstore.co.uk/photobook-the-history-of-photography-in-pen-and-ink.htm

¹¹ https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/kennard-haywain-with-cruise-missiles-t12484

|

|

I think this was a case of the security guard being in the wrong job – or the right job but in the wrong place – he would be better employed as a security guard in a High Street bank where copies of signatures are deemed forgeries. All artists who wish to learn skills learn by copying – this is same across all creative disciplines.: student musicians learn by practising playing Mozart, student novelists learn by writing in the style of…, student dancers… etc etc. It’s about assimilating the learning from the learning of those who have learned before then bringing our unique individual insight to what we have assimilated. Sometimes that means bringing everything visibly to our work = evident homage, sometimes that means rejecting it all = homage but no thanks homage! It would take eternity to write a convincing thesis on whom artists have copied – because everything in one sense is copied and everything in another sense is unique. It’s more a question of how we interpret and language rather than a question of art.

Yes Kym, I agree that we all copy to some extent, whether conscious or not. We absorb so much during learning and research that some of that must be evident in whatever we produce. Isaac Newton said he achieved what he did by ‘…standing on the shoulders of giants’. p.s. I’m not sure what the last sentence is saying – is there a word missing?

Thank you, Derek re mentioning the last sentence – also thankyou for the post – it’s stimulating food for thought. I think what I mean is: yes, we have to think about our interpretation of what ‘copying art’ means to us because by asking we are really having to answer whether we are ‘copying ‘unconsciously or mendaciously – or simply to self-aggrandise or through sheer laziness because we cannot think up anything original. (The security guard believed he was right and the student believed she was right – both doing their ‘work’.) I copied some of German Expressionist James Ensor’s faces, painting them blatantly into my work and in the same piece of work collaged a small thankyou note to Ensor – which seemed appropriate rather than appropriation. And recently, I collaged a printed image of part of a Dr Lakra sculpture into another work which was direct unacknowledged appropriation which lessened the quality of my work and made me feel a fake (taking the easy route rather than expressing originality). It’s about being honest about the art one is making whilst not using that as an excuse for making art by simply taking… hope this makes sense!

Really interesting article. I am struggling with this for Digital Image and Culture. I have taken a number of images from the net and made a layered collage. On top I have text right across the whole composite image. The resultant image is not for commercial purposes. Am I infringing copyright law???

Nuala: I made a series (over 700 images) of digital collages that use all sorts of source material. Some mine (photographs, scans of drawings, scans of tracings of drawings, some downloaded and not mine). Hardly anything in the resulting work is untreated, though sometimes it can be subtle. There are probably things that are in breach of someone’s copyright, but making art and selling art are two different things. As Derek says, it’s a complicated and endlessly changing situation. I suspect that some of my pieces would upset the owners of some of the images, but I’m not sure they can stop me making them. They could – I think – stop me selling them or sue me for money earned. Which would be nothing. There’s a lot of common sense out there too. Passing something off – forgery / fakery – is one thing. Photocopying a picture of David Beckham, blacking his teeth out and putting his head on upside sown to advertise a gig is another. Unless something – perhaps inadvertently – makes a lot of money, it’s not often a big problem. An interesting case is the Beastie Boys LP ‘Paul’s Boutique’ as it’s seen as the last LP to be made unaffected by having to legally ‘clear’ samples in the way that happens now. That LP sampled so many major artists (Beatles included) that legal departments woke up. I bet there are loads of bootleg mixes of hip hip LPS that we’ll never hear because permission to use samples were declined.

Bryan has summarsied my rambling very well: it’s more about where and how you are using it. If it’s only on your learning log and that’s not public then nobody would know. As I suggested in the articles, credit the sources where you can so that they are acknowledged.

David Bowie blatantly and lovingly and respectfully appropriated

Copyright issues do keep nagging at me so this is a very useful article and it’s so helpful as well to have examples and all those reference links. Thanks Derek.

Thank you, this article came at the right time!