Are you a Romantic?

Do you ever yearn to get away from it all, to walk by the sea or sit on a mountain-top, to lose yourself in nature? Or to live the simple life, free from the rampant materialism of the modern world? Do you ever fear that science and technology may go too far? If thoughts like this ever cross your mind, you are, Peter Akroyd argued recently on BBC 4, indebted to the Romantic writers of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Without them, we would not have access to these sensibilities today.

William Blake raged against the “dark satanic mills” of the industrial revolution which despoiled England’s “green and pleasant land” and crushed the human spirit. Wordsworth sought out the wild and perilous landscapes of the Lakes and the Alps where he had intense experiences of the power of spirit “which rolls through all things”. The early poems of John Clare celebrate the freedom of the natural world. (Unable to freely wander the open countryside after the Enclosure Acts he fell into depression and madness and spent the last 24 years of his life in a lunatic asylum). Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein taps into early fears of what might happen when science tampers with nature. The contemplation of Nature opened up in these writers a capacity for imagination, individualism and intense emotion – from ecstasy to despair.

But haven’t human beings always felt the same about nature, and had access to these sensibilities? Gary Lachman, a writer of many books on consciousness (and founding member of the rock band Blondie) explains why this way of thinking had not been available before.

‘One the most remarkable shifts in human consciousness occurred in the late eighteenth century. It was then that human beings discovered nature. Now this sounds absurd. How could human beings “discover” nature? Human beings had been up against nature from the start, competing with other animals, struggling to survive, enduring difficult conditions, and, eventually, learning how to use nature’s forces for our own ends and benefit, creating what we call civilization. Clearly, “nature” wasn’t some foreign land that we stumbled upon only a few centuries ago. Yet in another sense, this is exactly what happened….….The essence of that change is that with it nature becomes an object of contemplation, not, as it had been, something either to avoid or to control. The reasons for this are complex, but basically, by this time mankind had more or less won the struggle against nature and could now sit back and appreciate it aesthetically.’ Read the whole article here.

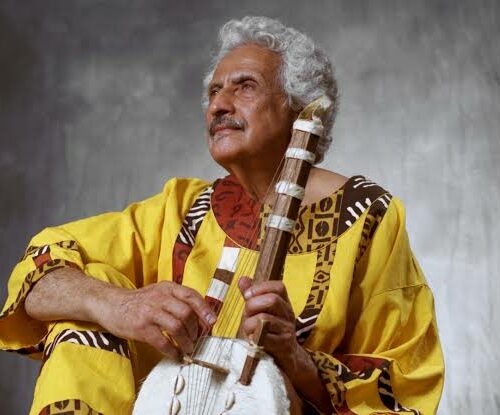

It was not only writers but artists and composers (Caspar David Friedrich (the image of the Wanderer above is by him), John Constable, Turner, William Blake and Brahms, Chopin, Mendelssohn). Their ability to convey this sensibility in poetry, paintings and music made access to these feelings and ideas widely accessible and changed the way we see and relate to nature.

Of course, the influence of the Romantics is not just limited to how we view a sunset or a beautiful vista. It affects our whole thinking and emotional response in relation to the mounting environmental crisis, to science and technology and to progress and the future in general. Do you believe that industrialism is “corrupt and inevitably leads to consumerism, alienation from nature and resource depletion.” If so, you are probably a Dark Green Environmentalist – a direct descendant of the Romantics. Or are you a Bright Green or even a Light Green Environmentalist? Check out the article What Shade of Green Are You? to find out!

I seem to remember reading somewhere that Blake’s “dark satanic mills” weren’t the factories, a bit nascent in his day, but the churches and particularly the cathedrals and the whole Jerusalem thing was as much a rail against the official Church of his day as the industrial revolution.

Wrestling with ideas of the sublime particularly the ‘post-modern sublime’ is particularly attractive to many of the current crop of artists and thinkers (take a look at Jameson’s work on post-modernism here )

I’m very interested in how the notions of the picturesque and the sublime affect our photographic vision – in landscape photography. The picturesque hinges on the predictability of aesthetic elements which you can safely ‘pick & mix”. The sublime, on the contrary, is based on the inherently unpredictable character of the natural world – hence its ability to invoke awe, fear and even horror. The sublime was a key concept for American Transcendentalists, who found a source of inspiration in the English Romantics.

In my opinion the picturesque (Gilpin’s picturesque) has more in common with a Newtonian mechanistic conception of the world that we may dare to acknowledge: it also introduces an strong element of control, in this case on the aesthetic experience. I would argue that photographic rules of composition are a legacy of it. We can extrapolate that element of control underlying the experience of the picturesque to the modern digital darkroom. Digital manipulations have allowed a revival of the picturesque. Nature is pre-arranged in the artist’s mind and re-arranged in the digital photograph.

Not sure where I’m going with this but I thought I would share it with you anyway 🙂

Anyway, for those interested in the wilderness vs. civilisation theme these are two excellent books:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Desert-Solitaire-Abbey/dp/0671695886/ref=sr_1_sc_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1320071594&sr=8-3-spell

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Wilderness-American-Mind-Yale-Nota/dp/0300091222/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1320071632&sr=1-1

And for something a bit more local

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Edgelands-Michael-Symmons-Roberts/dp/0224089021/ref=pd_sim_b_6

Last weekend I went to a talk hosted buy the RPS in Bradford, featuring Ian Beesley and John Davies, and both referred to the “dark satanic mills” of Blake, but with different readings. Beesley came up with the “mills” referring to the old English meaning of stone circles used for religious purposes, Davies spoke of the munitions factories and general warmongering attitude of the British (which feeds his latest work on war memorials and such like).

As for green, I’m probably a DPM green – grey in places, light in others and with a touch of whatever else seems appropriate at the time.

I’m definitely a mid dark green. i live on a mountain in the Pyrénées where it is fairly easy to be so but come to London often. That makes me despair as any shade of green is harder to achieve here although there are little pockets.

i don’t think I’m a Romantic though. it seems to me that green-ness is going to be essential for the survival of the planet – or at least for the survival of the human race on it.

Being environmentally responsible doesn’t have very much to do with Romanticism.

As for the article by Lachman, I couldn’t decide whether his comments like ‘mankind had more or less won the struggle against nature …’ were meant to be ironic or not. Surely this subject reaches (or ought to) further than the limits of art culture in the west? Am I the only one to find the whole argument highly dubious? Do we really believe that the pinnacle of human experience in our natural environment (the one we originally evolved in) begins and ends in the west?

My understanding of cultural concern with nature such as with the Romantics, is that artists were responding to something they saw threatened and beginning to disappear. The Romantics have surely helped in preserving our sensibilities yet I can not help but feel we would still have some notion of nature’s worth even though they might not be so well considered.