Just Kids: III

Long before either of them began producing significant work Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe were spotted by a couple of tourists out walking in the East Village. ‘Take their picture, I think that they’re artists,’ exclaimed the woman excitedly. ‘Oh, go on,’ her partner replied more cynically, ‘they’re just kids.’ For Patti Smith the incident seems an extraordinary coincidence in an almost miraculous life. As such, it is on a par with her bumping into Salvador Dali in the Chelsea Hotel, getting to know Sam Shepard without realising who he is or having Hendrix sit down and chat with her outside a party of his that she is too shy and nervous to attend. Then, of course, there was her meeting with Robert Mapplethorpe himself. For not only was he almost the first person that she met in New York but he reappeared and pretended to be her boyfriend just at the moment when she needed to get rid of an unwelcome suitor.

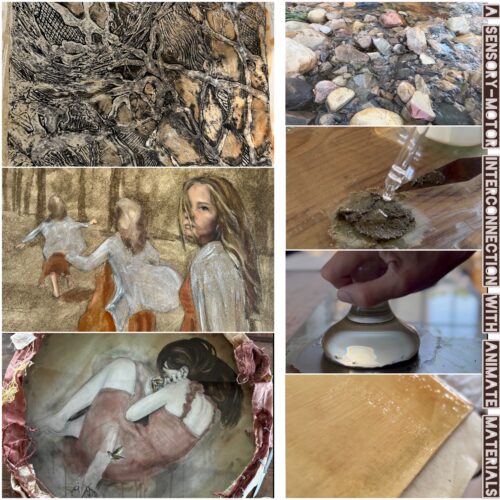

For readers who might be less willing to share Patti’s belief in ‘the hand of Fate and the hand of Providence’ there may be two alternative explanations. The first is that the photographer might have intuitively recognised the courage and naiveté of the pair whom Patti herself describes as ‘Hansel and Gretel venturing out into the Black Forest of the World’. The other is that Patti and Robert’s might indeed have been expressing themselves as artists since by the late sixties performance and appearance were increasingly important to contemporary art practice. Indeed they would continue to be so as part of a wider interrogation of image and identity throughout the punk period. Of course, young people such as the Teds, the Beats or the Rockers had long defined themselves according to what they wore. Yet what was significant about the sixties and seventies was the way in which fashion became part of a shift in emphasis from the way in which art was created to the way in which it was consumed. In the visual arts some practitioners ceased to regard themselves as visionaries or technicians and began to regard their personal statements as less important than their manipulation of a shared visual language. Some borrowed materials and techniques from industry; others used the reductive vocabulary of minimalism while a third group took images from popular culture. Yet the common factor was that all three deliberately undermined the notion of authorship.

In Just Kids Patti Smith mentions her awareness of Dan Flavin, Brice Marden and Roy Lichtenstein who between them demonstrate each of these approaches respectively. Yet the artist most associated with this transition was Andy Warhol and, although Patti Smith was part of his magic circle at Max’s Kansas City and the Factory, she goes out of her way to distance herself from him. ‘I hated the soup and felt little for the can’, she remarks, ‘I preferred an artist that transformed his time not mirrored it.’ Interestingly, it is in her response to Warhol and to the fashion for irony and for a use of appropriated and ready-made images in which he excelled that she seemed most distinct from Mapplethorpe.

At the start of their careers there seems to be little difference in her approach. An example of this is the self-portrait in a black hat that Robert took of himself in an automatic photo-booth and that he presented as an image that was not just of him but by him. In the same period Patti made a version of de Kooning’s Woman I that she implies is not a copy but a new reading of the work in the same way that she describes her reinterpretation of songs such as Hey Joe or Gloria. Even more significant was the photograph that they paid an anonymous Coney Island photographer to take at about the time that the two of them were spotted in the East Village. Mapplethorpe enlarged the photograph and included it in his exhibitions while she used it for the cover of her earlier memoir, The Coral Sea. When they first moved into the Chelsea Hotel she was writing poetry that she never performed while he was making jewellery, tearing collages from men’s magazines and assembling kitsch installations in the privacy of their room. His admiration for Warhol whose magazine, Interview, he contributed to in 1970, is shown by his drawings of cigarette packets which imitated Warhol’s use of commercial packaging. The contrast with the more grandiose statements that were being aired outside their door is suggested by her recollection that the hotel lobby was filled with ‘bad art….big invasive stuff that had been unloaded on the owner Stanley Bard in exchange for rent’.

As late as 1974 when they had joint show at an uptown gallery she exhibited pencil drawings which she implied that she had created quickly between gigs while on tour. By this time, however, he had moved on to a more glamorous circle of friends and to a much more technically sophisticated approach to materials. This was prompted in part by his friendship with John McKendry, the curator of photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not only did he introduce Mapplethorpe to such luminaries as Marisa Berenson and Bianca Jagger but he replaced his Polaroid camera with a Hasselblad and gave him access to the museum store. Suddenly, as Patti remarked, Mapplethorpe discovered that photography was ‘all about light’. Shortly afterwards his nudes started to resemble the glossy textures and intense contrasts of artists such as Edward Weston. Close-ups of the male body are presented in a fragmentary and fetishistic way. Yet the later work, while superficially shocking, is slicker, colder and more distant. Images like the The Snake Man, with their obvious references to Caravaggio, appear deliberately self-conscious, melodramatic and contrived.

It is interesting to speculate how much the divergence in their work was also influenced by Mapplethorpe’s acknowledgement of his homosexuality. Early on in their relationship he presented his sexual encounters with men simply as a way of earning a living through hustling. When he began his affair with David Croland, however, Patti described how he took down ‘the romantic chapel’ that he had created in their room and replaced it with less sentimental and more contemporary Mylar. As Patti remarks, ‘the velvet backdrop of our fable had been replaced with metallic shades and black satin.’ Implicit in her comment is the recognition that her ‘tousle-headed shepherd boy’ had discovered a different tone of voice as well as a different visual vocabulary. In this way images such as The Snake Man may also parade Mapplethorpe’s continuing exploration of a variety of sexual roles.

Perhaps, however, the difference between their artistic visions was apparent much earlier. For example, in 1969 when they saw the Christmas billboard that John Lennon and Yoko had put up urging New Yorkers that ‘War is Over if you want it’, Patti recalled that ‘Robert was interested in the medium and she in the message’. Describing the works that he made with a 360 land camera, she recalls that he spread a ’pink waxy coating over the image’ and ‘covered them in white emulsion’. He also presented these Polaroid works in elaborate frames or albums. Such devices drew attention to the lack of control that he had over the actual production of the image since the camera that he was using had no light meter and only limited settings. Perhaps, he took the idea of the frames from reliquaries and lockets since he had used a great deal of Catholic imagery in his earlier installations. Yet, whatever their sources, the use of kitsch distances the viewer from the subject matter and seems to place it in inverted commas. The same is true of Mapplethorpe’s presentation of models and poses from gay pornography in a fine art context. The viewer is able to indulge and excuse his voyeurism since the gallery creates an ambiguous context for the images but does not rob them of their edge.

The commercial imperatives of the visual arts encouraged Mapplethorpe to address his images to a sophisticated and exclusive market. In contrast Patti’s increasing involvement in the music industry meant that she was able to work in a more simple and straightforward manner. Indeed it was her passion and sincerity as much as her desire ‘to infuse the written word with the immediacy and frontal attack of rock and roll’ that propelled her so suddenly into the mainstream of the punk movement. Writing of her feelings in 1974, she says that she wanted to get away from contemporary music’s ‘spectacle, finance and vapid technical complexity’. The comment echoes Tommy Ramone’s claim that by 1973 he knew that ‘what was needed was some pure, stripped down, no bullshit rock ‘n’ roll’.

Patti’s mixture of poetry and rock was typical of punk’s collision of different idioms. At times her courage was breath-taking. Blessed with an uncanny absence of stage-fright, she took constant risks with improvised and spontaneous in performances. As John Holmstrom, the founding editor of Punk magazine, recalled a little later ‘punk was rock and roll by people who didn’t have very much skills as musicians but still felt the need to express themselves through music’.In 1976 an English fanzine took a similar approach by publishing an illustration of three chords with the caption ‘This is a chord, this is another, this is a third. Now form a band’.

Punk’s abrasive do-it-yourself philosophy helped to transform the relationship between musician and fan. No longer were the people on stage inaccessible rock-gods: instead they threw themselves out into the audience or indulged in protracted bouts of mutual insults or spitting. Not since the days of skiffle had young people been encouraged to create their own culture. In a world dominated by computers, smart phones and social networking, people can now create and exchange information at the touch of a button. Hence it is easy to forget how revolutionary such engagement then seemed.

I’m looking forward to reading your book. These have been excellent to read.

At one point, Patti Smith mentions seeing a photobook in a shop window; it called Love on the Left Bank. This book was first published in 1956 and is set in Paris at a time of revolutionary change. It is regarded as a seminal photobook and has since been republished by Dewi Lewis Publishing.

I bought the book for my Kindle, as recommended, and found it very interesting. I knew very little about Patti Smith and her poetry and music but found the book very evocative of the time. It is very readable and, in a way, written very innocently (or naïve?).