The densest things we ever see…

Drawing and paintings are typically results of addition and subtraction. Although this text focusses on the visual, throughout the first part parallels with the act of writing could easily be drawn, but any such reading is left to the reader. It should be noted that simple, gestural works (typically line drawings), are often unrevised and fall outside the remit of this review.

Drawing and paintings are typically results of addition and subtraction. Although this text focusses on the visual, throughout the first part parallels with the act of writing could easily be drawn, but any such reading is left to the reader. It should be noted that simple, gestural works (typically line drawings), are often unrevised and fall outside the remit of this review.

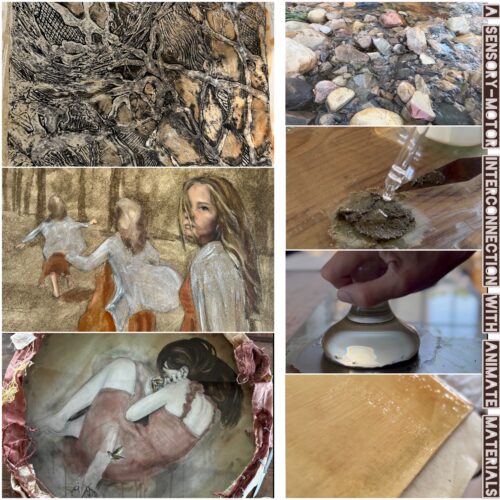

A work of art is often the result of a process in which successive layers are applied, edited, partially erased or removed wholesale with material accreting to form the visible surface of the work. While I will be writing in literal terms, it’s easy to read the preceding sentence as a metaphor.

Not all changes made to drawings are to remove or conceal errors; making a complex work is likely to involve the repeated re-balancing of tone, shape, and line. That is to say, the act of drawing is a dialectical one with each mark changing the field on which it is placed, forcing a reconsideration of the mark itself. This is why it is so difficult for any work not rooted in spontaneous gesture to ever be considered finished; something can always be tweaked. This process imparts in the work a richness in that a palimpsest is created. Certain artists – Alberto Giacometti and Frank Auerbach, for example – exploit the build-up of pentimento to make their drawings. Henri Matisse’s rhythmic drawings also depend on added and removed marks.

What, then, of the surface? Paint is generally thicker than graphite, meaning that a thick surface – impasto – is more likely or obvious on a painting. With passages of thick and thin paint, it is relatively easy to see the labour expended in the making of a painting. If we look closely at any of Claude Monet’s large waterlily paintings it is immediately apparent that the paintings’ terrain contributes to how some marks are made and that what underlies the visible surface contributes to what we can see: laden brushes, dragged lightly across the surface, catch on peaks of paint already applied to make marks that would be difficult (or impossible) to realise any other way.

Though drawings are, as has been mentioned, generally less thick than paintings much of what has been described is simply more easily noticed on painted work. Pencils, though, can cause particular material changes to substrate: denting and furrowing paper and, when blended or smudged, a polished look can be achieved that turns a black surface into one that is shiny and reflective. Using different kinds of eraser will affect graphite in different ways, too. Harsh erasing, for example, can scrape away the paper’s surface affecting how the pencil mark will be taken.

Most of our encounters with art are compromised, being via reproduction, whether digital or in print. These are encounters with flat, smooth (and possibly backlit), sources that lack bumpy, textured surfaces which catch the light or cast shadows. Images converted to jpegs are doubly cursed, as they are likely to have been subjected to ‘lossy’ compression which sacrifices detail, sometimes harshly, in favour of a small file size. When we encounter works of art first-hand (and there is something irresistibly delicious about that phrase in this context), the time spent and effort of making becomes apparent. A slick photographic reproduction eliminates the temporal by collapsing the works’ layers onto one simplified picture plane, as well as shrinking the image to a much more manageable size. I was once told by a sculptor that there were only three sizes that artists need worry about: smaller than us, our size, and bigger than us. This might also be expressed as looking down, across or up. Reproductions are invariably smaller than us or ‘down’. Flattening and shrinking coerces the viewer into understanding the image in one ‘hit’, as it were, depriving us of the possibility of what we might call an exploratory gaze that shifts between registers. David Pye, in his book The Nature and Art of Workmanship calls the variance in what is revealed in relation to perceptual distance ‘diversity’. Although his principle example is architectural, valorising the builder’s contribution to the ‘micro’ that works in tension with the architect’s ‘macro’ vision, it is possible to co-opt this term for works made by a single author. As one approaches a Rembrandt self-portrait one might be struck by the humanity of the face, but by nearing the painting the brushwork and glazing become more apparent. We might consider what is revealed close-up to be technical rather than rhetorical; I think that would be a mistake. It is in the labour and effort that we connect most closely with what the artist did.

Seeing works of art close-up can be overwhelming and disorientating, not simply because of any supposed importance or richness in terms of subject matter, but simply because they are often the densest things we ever see.

Thank you for such a lovely, thought provoking article, Brian. I am one of these people who annoys gallery staff as I like to get really, really close to a piece of work, so much so that my nose is almost touching it. I like to lose myself in the marks and feel like I am making them. This can be exhilarating, especially when it is in a style i don’t normally employ or in a technique beyond my abilities. I am glad you refer to Monet’s giant water lily paintings. When I visited the Orangerie in Paris many years ago I spend about three hours in there reveling in the layers, marks and colours. I probably bought a few postcards afterwards, but that was a waste of money for reasons you state. On a recent trip to Florence, I got up close to bits of Vasari’s frescoes in the Duomo, but the other jostling tourists, keen to get to the top, meant that I could only linger briefly. Still, it was enough to make me realise the vast difference between seeing the whole from below, where it appears as a large, inverted cake with the icing falling off, and the close up versions of sugary Heaven and decay in Hell. I am reminded of the scene in ‘The English Patient’, where Juliette Binoche gets hoisted up close to some frescoes. How wonderful! That is a dream of mine. Does anyone know which frescoes they were and where?

The murals might be in the monastery at Sant’Anna in Camprena. http://www.camprena.it

I’ve only just got around to reading this – and love it!